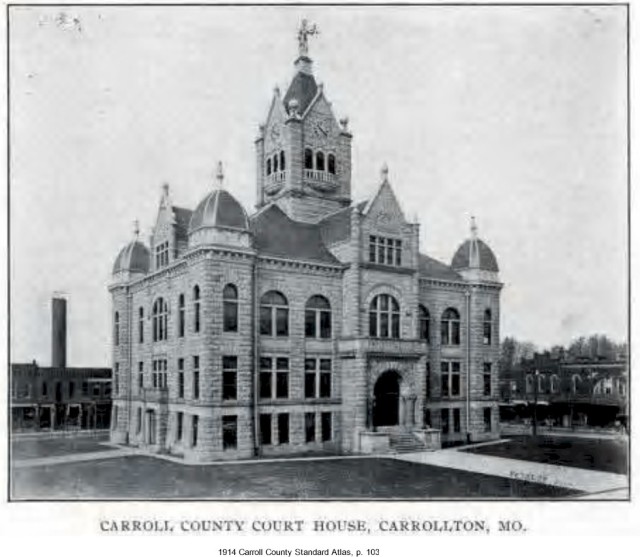

For lack of a better image from Carrollton, at present, I have chosen this old picture of the court house which is from the same era as the Wagaman family history presented here.

Opening an Onion: On the Nature of Family Secrets

An Essay by James Hart

For secrets are edged tools,

And must be kept from children and from fools. ~ John Dryden

Five years after her death, I learned my mother died with a secret; and now like a child or a fool, I fret about it with each passing year and tell myself I can never rest until I know it. Yet, since I can not know it, perhaps I can understand why she kept a secret. I believe I know what it is; but I will never know if it is true. I believe it should be true because of a minor anomaly that surfaced from little details of my mother’s life; and five years after discovering what I shall try to tell with some clarity, my intuition tells me I am right. I also sometimes wonder, can we ever really know someone? Even a mother. Perhaps. Perhaps not. Perhaps this is all an over-imagined fiction. Perhaps not.

To understand what I call the anomaly, you must understand that for the duration of my childhood, my mother almost made it a religion of family to teach her sons where her family members had all formerly lived in Carrollton, Missouri, where she grew up. As well, we knew where in the surrounding countryside various members of both my families had lived in previous decades. We knew the homes of dead people whose lives had been important to my mother during her childhood—even though they weren’t family. To name the locations of those people’s houses was to name the history of a place and how it connected to our family. Most importantly, of course, I knew where her childhood home on South Virginia Street stood, even into my adulthood, although during my childhood the house had long been a boarding house. To her it was home and always would be—her title of ownership was the nine-tenths of the law that comprised her memories of the house when she had lived there until her family lost it to foreclosure and financial ruin in the early years of the Great Depression. Everything else concerning the fate of that house was incidental to her, and eventually the same sense of possession of our family farm with its vanished house and barn would occur as easily to me in later years and in another world. But that’s a different story.

There is also the matter of the dead woman whose picture always hung on my mother’s living room wall on the farm and later on in her house in town. The woman’s name was Nadine Wagaman Elder, and she was my grandfather Floyd Wagaman’s first cousin. This is a detail which always confused me as a child, because my mother referred to Nadine’s sisters Grace and May as her aunts, even though they were her second cousins, because of their age differences and because of the roles they played in her own life. So, had Nadine lived longer, my mother might have referred to her as Aunt Nadine as well.

But that never occurred because Nadine died two years before my mother’s birth in 1918. Years later, Nadine’s ghost would seem to look down upon us from the picture in our living room—a fair-skinned young woman graduating from high school—her official portrait. Years later still, I would be able to identify a slightly older Nadine in my mother’s scrapbooks and photograph albums. One picture is especially poignant to me. My grandfather is behind the camera; my grandmother Mona is seated before a piano; Nadine and her husband, John Elder, are grouped behind my grandmother; he is holding his violin; a musical evening is in progress. Where is the room in this picture will never concern me until five years after my mother died.

I suppose a law of childhood is to ask what happened to the people in old family pictures when we do not know them or have no recollection of ever seeing them before. As with Nadine’s sister Grace, my mother told us when we were very young that she lived in a “hospital” in St. Joseph. When Grace died when I was twelve or so, I finally learned that she had spent the last years of her life in a mental institution; there were very few family members present for her graveside service at Oak Hill Cemetery. Grace had been away so long as to have been almost forgotten. In Nadine’s case, I remember asking when I was very young what had happened to her, and my mother’s answer was always “she died a long time ago before I was born.” And that had to suffice. Eventually, when we were “old enough” in my mother’s eyes, she told us Nadine had died in childbirth. With these details in mind, I don’t know what actually led my mother to telling us when I was fourteen how Nadine really died. I suppose we were finally old enough for the truth.

When she told us about Nadine’s death, I thought the details were horrific to imagine: Nadine had died of peritonitis after attempting to abort her baby with one of those long Victorian hat pins that many women collect today. To our astonished why, my mother explained that as a young woman Nadine was so proud of her girlish figure that she apparently couldn’t bear to ruin it by having a baby. Taking the matter into her own hands, she performed a deed we could barely imagine, and died later of blood poisoning. I don’t recall my mother telling us this with any particular moral in mind, only that we should finally know the truth about the pretty woman in the picture. And for years, I thought this was the truth. And it was the truth, as far as how she died; but the why is something I have been piecing together over eighty years later—a truth that is only an educated speculation.

One thing that supports my mother’s story about Nadine’s death is the shadowy lack of details in her obituary which is pasted into one of my mother’s scrapbooks:

MRS. JOHN T. ELDER DEAD

Mrs. Nadine Wagaman Elder, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W. H. Wagaman, was born in Carrollton, Mo., June 2nd, 1889. Her mother died when she was only six years old. The father kept the children together, the two older girls, Mrs. James McNish and Mrs. Arthur J. Meier, keeping house and being real mothers to their baby sister. She was the pet of the household and a general favorite with all the relatives. Her brother, Elmer, called her “Sunbeam,” for she was always like a ray of sunshine in the home. The family cannot recall a time when she was ever out of humor, and no one ever heard her speak unkindly of any one.

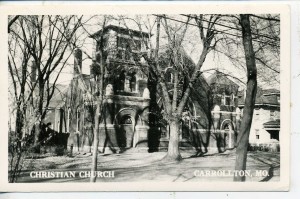

She attended the Christian church from her infancy, and accepted Christ as her Savior, April 14, 1902, under the ministry of the beloved E. H. Keller. The members of her church all loved her, both because of her beautiful character and the gracious way in which she responded to every call for service. She was one of the sweetest singers in the church choir, and she was one upon [whom] her pastor depended for music in funeral services.

She was married to Prof. John T. Elder, September 8th, 1915. This union was a most happy one, and their home life was ideal. They were planning and working for days of usefulness and happiness. A home had been purchased and was ready to be occupied, when the death’s messenger came, so suddenly and unexpectedly, that her wide circle of friends were inexpressibly shocked and grieved. For several weeks she had not been well, and had gone to her sister’s home, but her condition was not known to be serious until late last Monday evening, when she became much worse and gradually sank to unconsciousness and Tuesday at 11:40 p.m. she passed through the gates ajar, and was borne upward by the “Angels of Jesus” into the mansion of light.

It is hard to say goodbye to one so young and so fair, and whose presence meant so much to her family and friends. No one who knew her can doubt that all is well with her, and that she has gone to join “the choir invisible of those immortal dead who live again in minds made better by their presence.”

The funeral services will be held at the Christian church Thursday (tomorrow) at 3:00 p.m., conducted by Rev. G. L. Bush and interment at Oak Hill cemetery.

Christian Church, Carrollton

Christian Church, CarrolltonAmong the flowery Victorian prose compliments lavished on her by the writer is one missing detail: there is no mention of the “happy union’s” further tragedy of losing their prospective child. And eighty years later when I visited my mother’s former next door neighbor Georgia Lueders, a 93-year-old woman who remembered the Elders in 1915, and who most clearly remembered my grandparents’ “scandal” occurring in 1918, she had no memory of knowing why “Mrs. Elder” had died—only that she had. She could recall no hint of scandal associated with Nadine’s death and regretted the passing of her own older sister who might have known more. By the time of my grandparents’ hasty May marriage and the subsequent October birth of my mother, Georgia was 16 years old and remembered their marriage “caused quite a scandal” in Carrollton at the time. Enough so, that my grandparents were married in a neighboring town and moved to Kansas City, where my mother was born, and where my grandmother died three weeks afterward of influenza and pneumonia complicated by childbirth.

A few years ago, when I would finally question my mother’s only other living relative about the details of this story (my mother’s cousin Frances and the daughter of May and the niece of Grace and Nadine), she claimed to know nothing at all of such a shocking story. She asked tactfully how I could have heard such a story, or more pointedly, how could my mother have known such a story? To that I answered the only truth I know about it; my grandfather Floyd must have told my mother this story. And I believe now he must have done so in a moment of drunkenness. Why or how else could she have known? My grandmother certainly didn’t tell her; having died three weeks after my mother’s birth. My great-grandmother, being the “lady” I’ve heard her to be, probably did not tell my mother this story, even as a cautionary tale about “what happens” to young girls who get too friendly with men. I should add that Frances was eleven years older than my mother, which means she was also a girl of eight or nine years of age when Nadine died. She remembered her aunt, but the story she was told was that Nadine died “in childbirth”—again, no sordid details. Most importantly, she was old enough to know where her Aunt Nadine’s house in Carrollton had been located—roughly two to three blocks away, and around a corner, from her own parents’ house on West Heidel Street.

Now, jump back in time to a moment of foolish generosity that I will always regret. Right after my mother’s funeral in early December of 1990, several friends and family members gathered in my mother’s house in Carrollton. Frances was among them. In the course of her visit, we discussed family memories, and I felt an overwhelming urge to give Frances something from my mother’s life to take with her. First, I gave Frances the brown and white bean pot that my mother said always passed between the two households with baked beans in it when she was a child. I also gave her the picture of Nadine in its sedate gilded oak frame that my mother had refinished herself before I was born. Frances was delighted with the gesture and left soon afterwards, telling us she would probably give the picture to one of her sons. I thought nothing further of this episode nor even thought to regret the gift of the picture until five years later.

By now the hapless reader will absorb things inherent in this story: there are other secrets embedded along the way, some of which I’ve known since childhood when my mother first told them to me. Others only came to light with time, and years after my mother was gone and could not confirm what I thought I had discovered. Another problem is inherent in trying to tell this story at all. It’s like opening an onion, I think, like peeling back a layer at a time until finally the sharp juices inside make the eyes smart. There’s the brown papery layer, like the fragile pages of newsprint glued in my mother’s scrapbooks; the semi-transparent onion skin layer like the careful wording of a dead woman’s obituary. There are the tough green-striped layers that pull away stiffly like a living skin—revealing the corpse of a curiosity lying below, and the moist shiny heart of the matter—and maybe the juices of a truth that somehow smells foul. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s only sediment and landfill, and my imagination is the dark ravine where it trickles and fills; or slag, filling with a density I can’t see through. Whatever it is, it remains the Cyclopean eye of my own imagination, and it focuses on a mirror, and in that mirror is a face asking only one question—why didn’t she ever tell me about the house and whose it was? And, of course, she knew whose house it was. That is the first irony here—the house can not be a coincidence.

Now it is time to focus on August and September of 1995. My mother had been five years dead, and nothing had been done to that point about her house in Carrollton and the bulk of possessions she had left behind in it. After a summer of sorting, pitching, cleaning, bundling, and everything else preparatory to having an estate auction, I had sold in September what I didn’t keep and had been spending many evenings perusing old papers, scrapbooks, and our family photographs—reacquainting myself with all these dead people whose stories I had absorbed as a child. I saw that I had a different picture of Nadine among them, not as beautiful as the framed picture I’d given away to Frances, but lovely in its way; and there were two copies of the picture of the Elders and my grandmother Mona Frye Wagaman at the piano, with the Elders’ names clearly written on the back of one in my mother’s handwriting from the 1940’s. Their names were another detail that settled to the back of my mind as the evenings of reading and sorting progressed.

Eventually, I started reading through the real estate abstract that described the history of the property on which my mother’s house had stood in Carrollton. I vaguely recalled her reading through it one evening in 1981, soon after she had bought her house at 305 West Benton and moved in. At the time she mentioned that it was full of old Carrollton history related to land ownership from the early days to the time Carrollton became a town around 1833, and it progressed through the Civil War and into the present day. I’m almost sure she said I should read through it sometime, but then she put it away later that evening, and I never saw the document again until I removed it from her bank’s lock box fourteen years later. Since realtors no longer require that abstracts be passed on to the subsequent owners, I was free to keep it for myself after I sold her house.

We hear people claim there are transfixing moments that suddenly throw a lifetime into focus, or a piece tumbles into place that finishes a puzzle, or in this case, the reading of an abstract became a key unlocking a house door I never knew existed. And once I passed through the door, there would be no answers, only more questions, one clear indication of a secret, and the shadowy substances of inferences and speculations. The key was clear enough: while reading through the ownership pages for the early years of this century, one name leapt off its page at me—James McNish, the Uncle Jim of all my mother’s girlhood stories of the family of cousins who helped raise her when her father was often too drunk to be very useful, and who looked out for her as her grandmother became older and finally died. My great grandmother died in the 1940’s, and my grandfather died in 1950, I was born in 1953, and I knew that Uncle Jim had died during my earliest childhood, but before I could remember him. I also knew the close connections he and his family had to my mother’s life—his wife, May Wagaman; and his sisters-in-law—Grace who died in the asylum; Nadine who died of childbirth, or self-abortion and blood poisoning, depending on who’s telling the story—his brother-in-law Elmer who called his baby sister “Sunbeam” and who with his own daughter and the McNishes fill a family snapshot taken when my mother was a baby held in my great-grandfather’s arms in 1919. Here was a name I knew too well, signing for a cancelled note on a Trust Deed on November 4, 1918, for the mortgage for a new home—for John T. and Nadine Elder. And the next sale identifies the seller as John T. Elder, “single and unmarried; widower by the death of his wife.” They had bought the house on March 16, 1916, and John Elder was later free of it, selling it on August 11, 1919.

And for a moment the Elders’ names seemed old and strange to me, yet vaguely familiar, like old ghosts from pictures perhaps, because they were not yet so close to the surface of my memory, as they are now. And thinking, thinking, why are these names familiar to me, I remembered the piano and my grandmother, the man with the violin, the face of Nadine who looks astonishingly similar, like sisters instead of cousins, to my grandmother Mona Wagaman. For there is another detail in the story, not that it’s a secret, but one I haven’t revealed yet, that my grandmother Mona Frye was also my grandfather Floyd’s second cousin, and thus a cousin of the Wagamans of Nadine’s family. But if I casually showed you the picture of the musicians, and said here’s a picture of my grandmother and her sister, you’d believe it were true. They look enough alike.

I suppose by now, I need to explain the house. My wife Denise and I both, in looking back on all these pieces of story, remember clearly enough that when my mother bought her house in Carrollton, it was quite sudden and as soon as the house came onto the market. Previous to that, we had joined her in looking over a variety of other houses, none of them seemed right to her, and she had often called on us to come and see another one. Until the house she bought, that is. For that one, she had telephoned to report she’d found her house, had already bought it, and when would we come see it and help her make plans for moving? At the time, it seemed sudden and decisive enough, but we gave it little thought, assuming when we saw the house that it suited her, it was in sight of my aunt and uncle’s house also on West Benton Street, and she was anxious to move off our farm and into town before having to spend a second winter alone out there. Overall, it seemed the thing for her to do.

Nor did it seem unusual at the time, that we would arrange her living room in town in much the same way as her living room on the farm: a new sofa and chairs, yes, but her Eastlake secretary in the same northwest corner of the room, and a walnut dresser without a mirror in the southwest corner of the room, with the oak-framed picture of Nadine hanging above it as it always had hung in our living room on the farm. Nothing odd about it at all—then. Today, I think otherwise; but I’m jumping ahead of myself. What I never knew at the time, and didn’t know until those five years after my mother’s death, is that we were moving Nadine’s picture into the house that was to be her new home sixty-five years earlier. The one mentioned in her obituary as “a home had been purchased and was ready to be occupied, when . . . death’s messenger came.”

Reader, try to imagine the feverish thoughts running through my imagination when I finally pieced together from memory that of all the family homes my mother had pointed out to us as children, Nadine’s house had never been mentioned—and therein lay the anomaly. Other anomalies proliferated quickly. Frances, who visited with us after my mother’s funeral and took Nadine’s picture with her, was entering the house she must have known was her aunt’s intended house. Frances was about nine years old when Nadine died, and her childhood home, recall, was only two or three blocks away from this house; and it was her father who had secured the mortgage for the Elders. Georgia’s astonishment in learning that the house next door to hers was the intended home of the Elders—Mr. Elder whom she remembered as a nice man who gave violin lessons, whom everyone called Professor, and who moved away from Carrollton for good shortly after selling the house. That Georgia was unaware of the house’s connection did not puzzle me as much as the silence of Frances about it.

None of this did my mother ever discuss with Georgia, nor did she ever tell us in the years while she lived there. Coincidence? Learning about the house while reading the abstract? Only in implausible novels. Discovering it by accident, and not telling us the wonderful irony of it? Again, coincidence; and greater irony lies elsewhere, as you’ll know soon enough. No, of course she knew. With my mother’s intense devotion to preserving all things family, including this piece of family history she obviously never told us, she bought the house without a second’s hesitation the moment it was for sale. Of that I have no doubt. But I still needed to find a rational explanation for why this must be so, and the only explanation that makes sense to me now is what comes of five years of mulling this over in my mind. And in reaching it, I may be guilty of slandering the memory of my own grandfather.

To know my grandfather, Floyd Parker Wagaman, is to assemble fragments I remember of what my mother said about him, to study his pictures intuitively, and to peruse the remnants in my mother’s family scrapbook and the writings in his Galley Three scrapbook of readers’ contributions to the Kansas City Journal-Post. These he collected from the column’s inception in 1928 and afterwards. With various plays on his name (W. Dyolf is one), Floyd contributed most of his items under the nom de plume of Ichabod Crane—why, I don’t know, nor do I remember if my mother ever said. I think it’s an amusing sounding name from a story he liked and served its use for him. The scrapbook is ninety pages of tidily clipped and pasted articles carrying on several years’ worth of comment and “conversation” among the regular contributors. To me, it is journalism Americana, a bridge to my grandfather’s mind, and priceless—scraps, pictures, memories, the layers of a man, or the skins of another onion.

And what are those layers? A dandy in pin-striped suits, a ladies’ man in the old-fashioned sense, a failed writer, an incurable romanticist, probably an inadequate father, an alcoholic, and late in his life a morphine addict—made that way by the Carrollton doctor who treated him for cancer in the last year of his life. Such qualities rolled together into one man whom I never knew, and who has fascinated me all of my life. A few years ago, it occurred to me that he might be a Richard Cory like in the Robinson poem, but without the useful gunshot at the end—only shots of whiskey instead. I even imagined him thus in my own poem “Whenever I Read Richard Cory.” One thing I remember my mother saying often over the years was how she sometimes poured his bottles of whiskey down the kitchen sink for his own good, and risking his certain anger later. Yet, of other women in his life my mother never said a word. I always assumed that my grandmother’s death so soon after my mother was born ended the great love of his life. And although she never actually said so, I believed my mother thought so too. But now I wonder otherwise.

Old pictures tell strange stories, especially without explanatory captions or scrapbook notes to provide the missing words. It’s 1910, and my grandfather poses for a self-portrait which he tagged “Beau Brummel of Carrollton, 1910.” The ladies’ man. It’s 1908, and the McNishes and my great grandparents and other guests are assembled on the lawn in front of the South Virginia Street house. Everyone’s in fine clothes, and the women are all wearing beautiful white dresses. The woman seated next to my grandfather in the group is not my grandmother, and she is not Nadine. Some faces over many years are quite easy to recognize at various times and settings, and some faces are not at all easy to trace through a series of years and pictures—Nadine’s is sometimes such a face. She sits in the same picture, among the other seated women, and her nose is unmistakably identifiable with her other portrait I have.

There is an album of pictures my grandfather put together over several years, and the early pages show him with another woman who is not my grandmother, and again who may or may not be Nadine. It is so hard to tell. But the woman is clearly his intimate friend—a couple posed as a couple leaves no doubt. Captions are not needed. As a child, I never knew about this album. I only acquired it from my mother’s effects after she died. So there it waited for me to ponder: who is this woman who is not my grandmother; this woman whom my mother never told us about? So many questions. Such apparent secrets. Imagine how carefully my mother had built a bridge back into her family for me to follow over; yet time showed some planks were always missing. Or an onion waited for me to start peeling through the acid layers until it stung my eyes. Which is it?

Do you see, reader, where five years of mulling and speculation are leading me? To a conclusion that seems inevitable to me—and slanderous. First, why does an apparently God-fearing, good Christian woman, of perhaps dubious saintly ways (who knows who wrote her obituary?), in the prime of her womanhood, recently married, and about to take possession of a new home with her husband, essentially kill herself by trying to abort her baby with a hatpin? A truth that only my mother told me. What leads an educated man who would have seemed to have everything going for him in his family background (the Wagamans did fancy themselves as upper middle class intelligentsia until the Depression ruined them financially) to become a sometimes self-employed dilettante, but mostly a miserable and embarrassing drunk and occasional burden to his widowed mother who helped him raise his only daughter? And what made my mother secretly enshrine the details of Nadine’s life and death in such a manner as I have outlined?

For enshrine them, she did. There was the framed picture to start with, and the antique walnut dresser over which it hung in two different homes—the kind of dresser that once had a frame attached for holding a mirror, and two small drawer boxes on each side of a central piece of white marble top. Another detail of the dresser has up to now been overlooked—that it belonged to Aunt May, as my mother always said, who gave it to her to use when my parents bought their farm. In 1954, to one set of eyes it was old cast-off furniture, worth a dollar at most; to my mother, it was an antique, made of beautiful wood, and a part of her family. For all I know, it may have been Nadine’s dresser—given back to her family by Mr. Elder after her death. I like to think it might have been; I suppose it could have been; but no one can know that now. And I know as a child, it never occurred to me to see something else about the dresser as decidedly odd—if not macabre. For over the years, my mother had collected a variety of long Victorian hatpins, some from my grandmother Hart’s belongings, some from garage sale or estate auction remnants—but hatpins nonetheless. Long sinister looking ones, like the one Nadine must have used to kill her baby, and she kept them in one of the small drawers under Nadine’s picture. The hardest part of this for me to believe now is that as a youth who had read plenty of Edgar Allan Poe, the significance of such objects in that dresser under that picture never occurred to me.

Such is our emotional relativity. Only in learning that my mother had bought Nadine’s house and moved her picture into it, did I see that a shrine had been returned to its temple, so to speak. And what was the religion celebrated in this temple? Family. So after peeling back all of the onion layers to the least bulb at the heart of it, what conclusion or speculation have I reached? My mother worshipped her family. My mother rued growing up an only child. My mother made a shrine of her dead mother’s cousin’s picture. My mother told tantalizing bits of a story over the years, but left out the best bit of all—explaining why. Or how she knew such a wretched story of a dreadful fate. I said my grandfather must have been the one who told her how Nadine died. Was there more?

Did he know that entombed beneath his life-long drunkenness was a pathetic and broken heart, not because his wife died giving birth to his only daughter, but perhaps because he had indirectly killed two women he loved? Cousins who could pass for sisters—that’s not imagination. And was my mother’s macabre shrine created for the half-sibling she never had in life—but knew of only in death? Do I understand why she kept a secret? I think so; how would one tell such a thing if it were true? Could such a story be secretly true? Yes, it could be; and so could secrets be edged tools, best kept from children and from fools.

Carrollton, North Side of Court House Square

Carrollton, North Side of Court House SquareWhenever I Read Richard Cory

James Hart

Whenever I read Richard Cory,

I see my grandfather stroll down town

long years before I knew his story,

and all eyes envied his haughty frown.

Dressed head to heel in dapper grays,

he tipped his hat like a lord for ladies

and made good day a grand regal phrase

that fluttered pulses to shy rhapsodies.

“Beau Brummel of Carrollton, 1910”

he dared inscribe on a sly self-portrait

where he casts his gaze beyond his ken

like a landless squire who beggars fate.

So it comes as no grim surprise to me

that he fired only words in his head,

and daily deadened his sad gravity

in shots of whiskey downed like lead.

Slight revisions made during

reading, on September 3, 2012.

Poem added to this manuscript

for reference purposes,

on September 3, 2012.

Somewhat the story of my mother…

I will have to print this post so it will be easier to read.

There is so much you have to read between the lines.

I can feel your sorrow as I try reading it on my monitor.

Did I tell you my grandfather was rich and lost everything to gambling?

Three times!

About family secrets… I could write a book about them.

I finally found a blogger I can relate to.

Thanks for posting.

Pierre

Printing done…

Final comment for the day…

About cemeteries…